A comprehensive review of inpatient falls written by Alison Schofield (Independent Tissue Viability Nurse), providing expert analysis on current trends and statistics.

Background

A fall is defined as an event which causes a person to, unintentionally, rest on the ground or lower level, and is not a result of a major intrinsic event (such as a stroke) or overwhelming hazard.

In-patient falls are the most frequently reported safety incident. More than 250,000 falls and 1,000 fractures are reported from hospitals each year in England and Wales. UK data shows an average of 6.63 falls per 1,000 occupied bed days, which equates to more than 1,700 falls in an 800-bed general hospital at current bed occupancy rates. Data also showed that 30 — 50% of falls resulted in physical injury, as well as fractures which occurred in 1-3% of patients.

Organisation Patient Safety Incident Reports (OPSIR) workbooks based on data submitted to the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) covering the period April 2018 to March 2019 reported 228,503 patient accidents in acute (non-specialist) hospitals in England and Wales. The vast majority of these patient accidents would be patient falls and the number suggest more than 600 patients fall every day.

As the population continues to age, the number of elderly people aged 80+ is expected to double from 3m to 6m by 2030. As people live longer, more elderly patients are being admitted to hospital, signalled by a 58.9% increase in admissions of those aged 85+. Winter pressures with increased issues such as the flu virus, covid new strains added into reduced staffing in health and social care, can cause ‘bed blocking’ in hospital wards also; longer stays, reduced mobility, further falls.

Every year more than one in three people over 65 suffer a fall, which can cause serious injury and even death. The costs to the NHS and social care from hip fractures alone are an estimated £6 million per day or £2.3 billion per year. The average cost per fall in hospitals is £2600 according to NHS improvement data (2017).

Harm from falls

Over 3 million people in the UK have osteoporosis and they are at much greater risk of fragility fractures. Fragility fractures are fractures that result from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in fracture, known as low-level (or ‘low energy’) trauma. The World Health Organization (WHO) has quantified this as ‘forces equivalent to a fall from a standing height or less’. Hip fractures alone account for 1.8 million hospital bed days and £1.1 billion in hospital costs every year, excluding the high cost of social care. The total annual cost of fragility fractures to the UK has been estimated at £4.4 billion which includes £1.1 billion for social care; hip fractures account for around £2 billion of this sum. Short and long-term outlooks for patients are generally poor following a hip fracture, with an increased one-year mortality of between 18% and 33% and negative effects on daily living activities such as shopping and walking. A review of long-term disability found that around 20% of hipfalls are the main cause of a person losing their independence and going into long term care. After a fall, the fear of falling can lead to more inactivity, loss of strength, loss of confidence, and a greater risk of further falls and a greater risk of death. Fracture patients entered long-term care in the first year after fracture.

Increases risk of injury and further complications

When a resident experiences a fall, immediate medical attention is crucial to assess the extent of injuries and provide timely treatment. It’s a proven fact that delayed response times can worsen the physical consequences of falls, leading to more severe injuries and complications.

Even if a fallen person hasn’t sustained any injury as a direct result of falling, they could develop an injury whilst lying on the floor for a long time. Some of the serious complications associated with long lies include:

- Pressure sores

- Dehydration

- Hypothermia

- Pneumonia

- Acute kidney failure

Care homes often default to calling the ambulance service to lift the fallen resident due to a lack of appropriate lifting equipment in the care home. With the ever-growing pressure on the ambulance service and the NHS, it’s more important than ever for care homes to manage minor and no-injury falls that occur in their own home, without having to call the ambulance service.

Cost analysis of falls per resident / patient with additional complications as listed; admissions, pressure ulcer treatment is required.

Average pressure ulcer costs is £4000 daily. Category 4 is estimated £15,000.

£3.8 million daily cost to the NHS of treating pressure ulcers.

The Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF) sets out the NHS’s approach to developing and maintaining effective systems and processes for responding to patient safety incidents for the purpose of learning and improving patient safety. This introductory Patient Safety Incident Response Framework responds to calls for a new approach to incident management, one which facilitates “learning” rather than as part of a “framework of accountability”. Informed by feedback and drawing on good practice from healthcare and other sectors, it supports a systematic, compassionate, and proficient response to patient safety incidents; anchored in the principles of openness, fair accountability, learning and continuous improvement. The new system is expected to be embedded by Autumn 2023.

Education and awareness for professionals and organisations

Older people coming into contact with professionals and organisations which have health and care as part of their remit should be asked routinely about falls. Older people reporting a fall or at risk of falling should be observed for balance and gait deficits and considered for risk assessment and risk reduction interventions. Relevant professional groups include primary, community and secondary care clinicians; allied health professionals; emergency ambulance crews; social workers; employees of voluntary and community sector organisations working with older people; and members of the Fire and Rescue Service (FRS). The development of workforce competencies and training may be necessary for a wide range of health and other professions.

New supporting evidence

NICE is updating the 2013 guideline to reflect changes in evidence related to falls in hospital, to encourage the uptake of similar measures at home and in social care settings, and to reflect national developments, such as the work of the National Falls Prevention Coordination Group. Guideline scope: Falls: assessment and prevention in older people and people 50 and over at higher risk.

Key areas to be covered in the NICE update:

Information and education about falls risk and prevention for people who are at risk of falls or who have had a fall, and their families and carers. 2 How to identify people at risk of falls for further assessment, for example: routine questioning, observation, screening tools, electronic patient records. 3 Risk factor assessment for people identified to be at risk of falls, for example: risk assessment tools, gait assessment, frailty indices. 4 Interventions to reduce risk of falls, for example: multifactorial and multicomponent interventions, exercise programmes, strength and balance training, medication reviews, home hazard and safety interventions, environmental modifications.

There are a large number of risk factors for falls. These include: – a history of falls – lower levels of strength because of a decline in muscle mass – impaired balance because of declines and changes in sensory systems, the nervous system, and muscles – polypharmacy and the use of psychotropic and antiarrhythmic medicines – visual impairment – environmental hazards – frailty.

There is an increased risk of falling among some people aged younger than 65, including those with underlying conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and diabetes. The update to the 2013 guideline will review methods of identifying people aged 50 to 64 who are at risk of falls in all settings (including homes and social care settings) and would benefit from preventative measures.

Calculating fall rates, inpatient settings

- Count the number of falls in the month.

- How many beds were occupied each day?

- Add up the total occupied beds each day for the month (patient bed days).

- Divide the number of falls by the number of patient bed days for the month.

- Multiply the results by 1,000 to get the fall rate per 1,000 patient bed days.

Example:

| Directions | Example |

| Count number of falls in April. | 3 falls in April |

| Count occupied beds each day in April. | 26 on April 1, 28 on April 2, … |

| Add up the total occupied beds each day for April (patient bed days). | 879 occupied beds |

| Divide the number of falls by the number of patient bed days in April. | 3/879 = 0.0034 |

| Multiply by 1,000. | 0.0034 x 1,000 = 3.4 falls per 1,000 patient bed days |

- Examine the rates for trends over time.

- Graph data in a run chart to visually examine.

- Are rates getting better or worse?

- Can you relate changes in rates to changes in practice?

- Rates are probably quite different by patient unit.

- Focus on trends over time. There will be fluctuations.

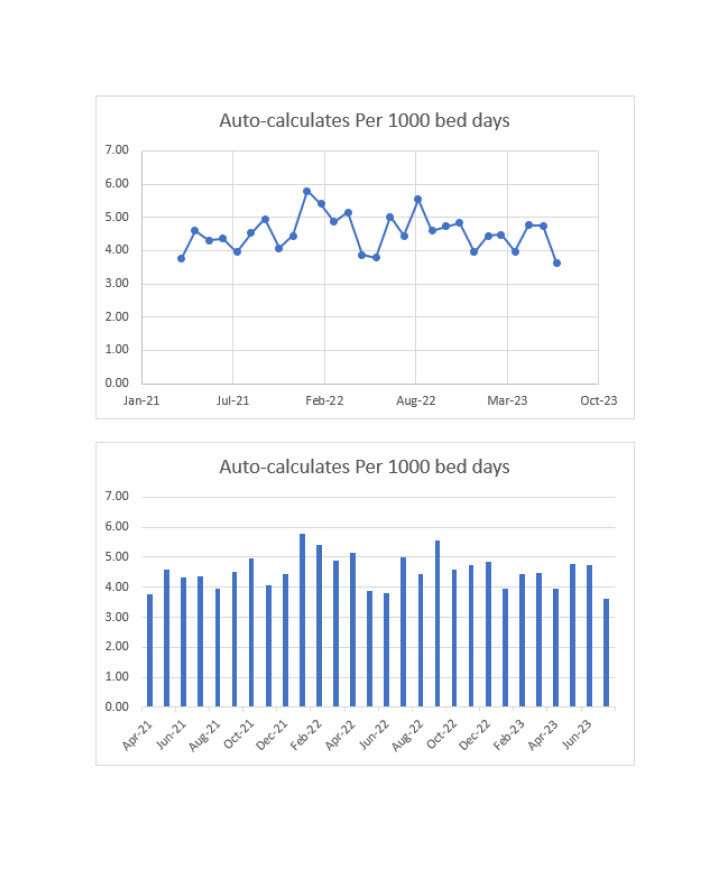

One NHS Hospital Trust falls date April 2021 — July 2023. A 1,268-bedded teaching hospital.

Analysis

The mean falls per 1000 bed days in the UK is 6.63, therefore this Trust data is below average. There are some noted peaks close to the average during winter months, data covers April 2021 to July 2023. Peaks correlate with winter pressures, recent staffing issues and ongoing effect of the Covid 19 pandemic.

Root cause analysis investigation looks to provide thematic analysis for falls data and creation of lessons learned targeted interventions and education.

References

- Graves N, Birrell F,Whitbt M. Effect of Pressure Ulcers on length of Hospital stay . Cambridge University Press on line(2016)

- Morris, R., & O’Riordan, S. (2017). Prevention of falls in hospital. Clinical medicine (London, England), 17(4), 360—362.

- Falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention | Guidance and guidelines | NICE [Internet]. 2013

- Royal College of Nursing – Falls Report

- National Audit of Inpatient Falls, Royal College of Physicians. 2015

- Pressure ulcers: revised definition and measurement, NHS Improvement, 2018

- NICE Costing statement: Pressure ulcers, 2014

- Pressure ulcers: productivity calculator, Department of Health and Social Care, 2010

- Pressure Ulcers to Zero, National Quality Improvement Team, 2018

- National Stop the Pressure programme: One year on — our focus for improvement, 2017

- Oliver D., Healey F. & Haines T. Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in hospitals. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:645—92.

- Falls: applying All Our Health – Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) Guidance

- Vincent C, Amalberti R (2016) Safer healthcare — strategies for the real world. Springer.

- World Health Organization Falls Report